Comparative Anatomy

Need more convincing? Comparative anatomy provides more important and compelling evidence for evolution. Ready for a field trip? We're off to the zoo. Well…we're going. You'll just have to pretend.

Upon arriving at the zoo, we immediately hit the concession stand for some popcorn, or maybe one of those giant roasted turkey drumsticks, because anatomy is best enjoyed with a snack. We proceed immediately to the primate enclosure, where some New World monkeys jealously eye what's left of our food. If we look closely, we'll notice that they have a lot in common with us—their faces, their little hands, the shape of their skulls. Even the biggest evolution doubters have to admit that compared to a dog or a flamingo or a snake, we have a LOT in common with monkeys.

Next, we move on to the reptile house, where we check out a giant tortoise. Unlike the monkey, the tortoise has a lot of features that we just can't relate to. Its skull is pretty small compared to the rest of its body; it has thick, scaly skin, and what's up with that shell?

Still holding the remains of our turkey drumstick (mostly just the bone now), an idea suddenly occurs to us: despite the differences between humans, monkeys, tortoises, and that unlucky turkey we just ate, there are some features we all have in common. For example, we all have two arms and two legs, skulls, vertebrae, and ribs.

There's a reason we all have these similar anatomical structures: they are homologous, meaning they arose from a common ancestor. Sure, our long supple legs look pretty different compared to the stumpy tortoise, but that's because organisms change over time to adapt to different environments. But originally, these homologous structures came from an ancestor we all shared.

The bones that make up our arms are pretty similar to those of a turkey's wings. The bones that form the ribcage in humans, monkeys, and turkeys actually make up the tortoise's shell. Go back far enough in our time machine, and we could find the last common ancestor between tortoises and humans. The same bones were used to provide shelter and protection to tortoises eventually morphed to make up the rib cage in humans.

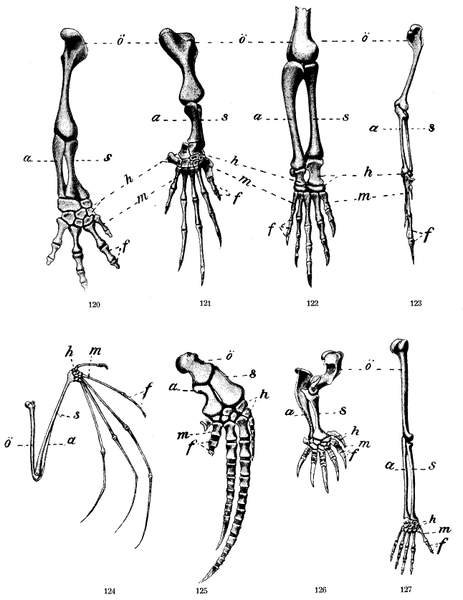

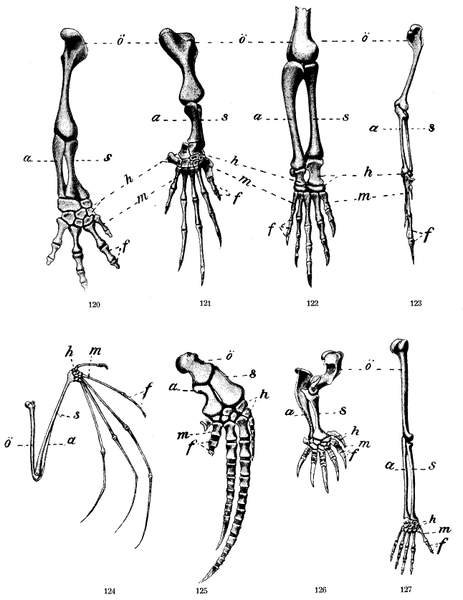

From left to right: (top) salamander, sea turtle, crocodile, bird; (bottom) bat, whale, mole, human. (Source)

If these structures all look so different due to millions of years of evolution in wildly different environments, how do we know they're homologous to each other? How can we be sure they came from a common ancestor? Let's use one of the lower leg bones (tibia) as an example. We can tell tibiae are homologous in humans, monkeys, tortoises, and turkeys because they always connect with the upper leg bone (femur) and the bones of the foot, and similar muscles connect them to other bones.

There are certain bumps and grooves on all the tibiae, and although those features might be a little different from tibia to tibia, they're there, and in roughly the same places. Finally, scientists who study development know that the tibia originates during fetal development in the same way in all these different animals. All these lines of evidence support the conclusion that tibiae are homologous in humans, monkeys, tortoises, and turkeys—that is, a long time ago, a common ancestor had a tibia, and over time, evolution has modified the tibia for different animals in different environments.

Vestigial structures are another class of anatomical features that provide evidence for common ancestry and evolution. Vestigial structures serve no apparent purpose in species that possess them at present, but may have been important in their ancestors. For example, whales have hip bones, but they don't need them, since they can't exactly go for a stroll. These hip bones are as useless as nipples on a fish (point of fact, fish don't have nipples). However, the fact that whales have hip bones even though they don't need them suggests that their ancestors might have had a use for them and walked on land.

Bottom line, comparative anatomy shows how we actually share many fundamental similarities and evidence strongly supports the idea that these similarities are derived from a common ancestor. The differences we see in modern organisms are the result of changes over time, as organisms adapt to their environment. Hooray evolution!

Upon arriving at the zoo, we immediately hit the concession stand for some popcorn, or maybe one of those giant roasted turkey drumsticks, because anatomy is best enjoyed with a snack. We proceed immediately to the primate enclosure, where some New World monkeys jealously eye what's left of our food. If we look closely, we'll notice that they have a lot in common with us—their faces, their little hands, the shape of their skulls. Even the biggest evolution doubters have to admit that compared to a dog or a flamingo or a snake, we have a LOT in common with monkeys.

Next, we move on to the reptile house, where we check out a giant tortoise. Unlike the monkey, the tortoise has a lot of features that we just can't relate to. Its skull is pretty small compared to the rest of its body; it has thick, scaly skin, and what's up with that shell?

Still holding the remains of our turkey drumstick (mostly just the bone now), an idea suddenly occurs to us: despite the differences between humans, monkeys, tortoises, and that unlucky turkey we just ate, there are some features we all have in common. For example, we all have two arms and two legs, skulls, vertebrae, and ribs.

There's a reason we all have these similar anatomical structures: they are homologous, meaning they arose from a common ancestor. Sure, our long supple legs look pretty different compared to the stumpy tortoise, but that's because organisms change over time to adapt to different environments. But originally, these homologous structures came from an ancestor we all shared.

The bones that make up our arms are pretty similar to those of a turkey's wings. The bones that form the ribcage in humans, monkeys, and turkeys actually make up the tortoise's shell. Go back far enough in our time machine, and we could find the last common ancestor between tortoises and humans. The same bones were used to provide shelter and protection to tortoises eventually morphed to make up the rib cage in humans.

From left to right: (top) salamander, sea turtle, crocodile, bird; (bottom) bat, whale, mole, human. (Source)

If these structures all look so different due to millions of years of evolution in wildly different environments, how do we know they're homologous to each other? How can we be sure they came from a common ancestor? Let's use one of the lower leg bones (tibia) as an example. We can tell tibiae are homologous in humans, monkeys, tortoises, and turkeys because they always connect with the upper leg bone (femur) and the bones of the foot, and similar muscles connect them to other bones.

There are certain bumps and grooves on all the tibiae, and although those features might be a little different from tibia to tibia, they're there, and in roughly the same places. Finally, scientists who study development know that the tibia originates during fetal development in the same way in all these different animals. All these lines of evidence support the conclusion that tibiae are homologous in humans, monkeys, tortoises, and turkeys—that is, a long time ago, a common ancestor had a tibia, and over time, evolution has modified the tibia for different animals in different environments.

Vestigial structures are another class of anatomical features that provide evidence for common ancestry and evolution. Vestigial structures serve no apparent purpose in species that possess them at present, but may have been important in their ancestors. For example, whales have hip bones, but they don't need them, since they can't exactly go for a stroll. These hip bones are as useless as nipples on a fish (point of fact, fish don't have nipples). However, the fact that whales have hip bones even though they don't need them suggests that their ancestors might have had a use for them and walked on land.

Bottom line, comparative anatomy shows how we actually share many fundamental similarities and evidence strongly supports the idea that these similarities are derived from a common ancestor. The differences we see in modern organisms are the result of changes over time, as organisms adapt to their environment. Hooray evolution!