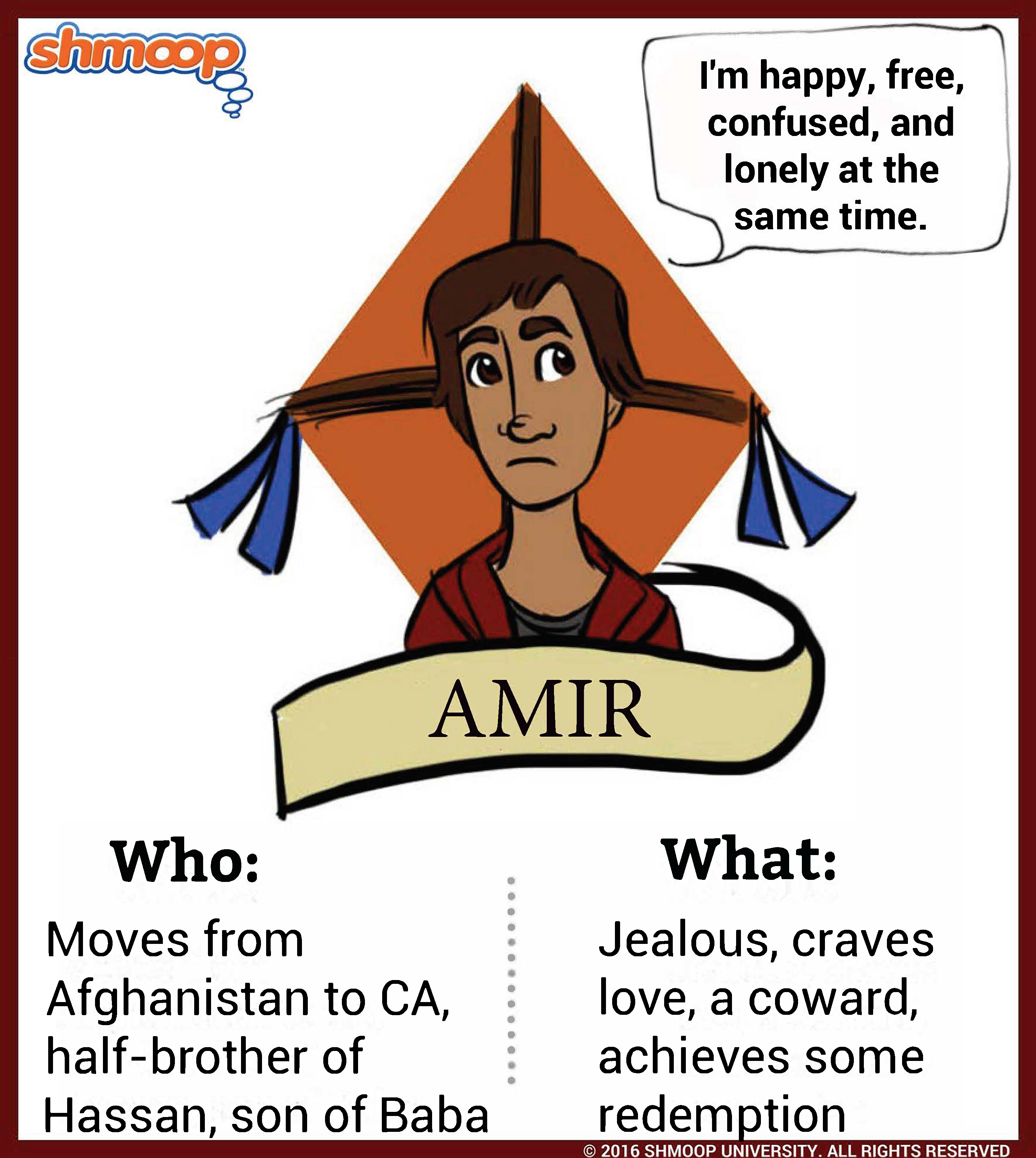

Character Analysis

(Click the character infographic to download.)

Like most good narrator-protagonists, Amir is a fairly complex character because the reader not only has to pay attention to Amir's actions but also how Amir describes his actions. Plus, Amir grows up, changes, and is affected by where he's living – whether that's Afghanistan or California. With this in mind, we analyzed Amir's character in each of the major settings of the novel. As we've stressed elsewhere, some really major events happen early in the novel. Thus, we'll spend the bulk of our time on Amir's childhood.

Amir the Boy in Kabul, Afghanistan

When the novel first describes Amir's childhood, it seems like Amir leads a relatively charmed life. He's got a great friend in Hassan, his father is wealthy, he adores his father, etc. We would like to pause here and praise the innocent joy of the first years of Amir and Hassan's friendship. Sure, there's jealousy and some cruelty and power struggles. But there's also adoration, loyalty, and genuine affection between the boys.

OK – on to more pain and suffering. Most of the early conflict seems confined to the lives of Ali and Hassan. There's racial discrimination toward them, Sanaubar leaving, Hassan's harelip, and the soldiers' taunting of Hassan.

We soon learn, however, that Amir has anything but a charmed existence. Amir's mother died giving birth to him. It's clear he feels a great lack in his life, and he throws himself into poetry and writing, we think, partly as a tribute to her. In addition, Amir feels an enormous amount of responsibility for his mother's death – as if he not only caused it but, more sinisterly, was responsible for it. Worse (can it get much worse?), Amir begins to believe his father also blames him for his mother's death. This is only one aspect of the incredibly fraught relationship between Amir and his father.

Amir is also extremely jealous of his half-brother Hassan. (At this point Amir doesn't know Hassan is his half-brother and that knowledge probably would have tempered Amir's jealousy.) Amir admires Baba to no end although Baba seems to have little time for Amir. In fact, at times it seems like Baba prefers Hassan. Baba is almost confused by Amir. How can his son not like violent Afghan sports? Why does Amir not stand up for himself? And so on. Most of Baba's complaints seem to spring from Amir's lack of "manliness."

All these tensions come to a breaking point during the kite-fighting tournament. Amir sees the kite-fighting tournament as a way to finally win Baba's love. Amir concocts this mad scheme where he'll win the tournament. Then Baba will love him and everything will be hunky-dory.

The strange thing is that Amir's plan sort of works. Amir wins the tournament and his father finally shows the boy some love. But that's not all that happens. Amir happens upon a horrific scene in the alleyway while looking for Hassan, who has just run down a kite, the crowning jewel of Amir's kite-fighting victory. While two neighborhood boys hold down Hassan, a nearly-demonic boy named Assef rapes Hassan. Amir watches this happen and does nothing.

It's tough to understand exactly why Amir doesn't help Hassan. Is it because he wants Baba's love all for himself? Because Hassan is a Hazara and thus "inferior"? Because Amir is simply a coward? Perhaps all of these motivations combine into one great instant of paralysis. Worse, after Amir sees a hollow-eyed Hassan around the house in the months following the rape, Amir falls apart and betrays Hassan again. He has to remove any reminder of his guilt. So he plants a wad of cash and watch under Hassan's mattress, framing him for theft, and driving Hassan and Ali out of Baba's house.

We don't think the rest of the novel really uncovers Amir's motivations. Hosseini takes the novel on a different track. He has Amir slowly change and attempt to make up for his moral failure. Perhaps this is the only thing Amir can do: what would more thinking and inaction accomplish? Isn't the remedy for passivity some sort of swift action? Sure, but it takes Amir thirty years to redeem himself, and even then we're not entirely sure it's enough.

Amir the Young Man in Fremont, California

Something really changes in Amir when he and Baba arrive in Fremont. Perhaps it's because Amir adapts easier to living in the United States. It could be that Amir no longer sees Baba as a legendary father and simply as a father. (Baba has to work long hours in a gas station and loses some of the mystique he had in Afghanistan.) Or maybe Amir is able to forget about his betrayal of Hassan. Somehow America allows him blankness, a forgetfulness that would be impossible in Afghanistan.

Whatever the case, this is a different Amir. He takes care of his father, meets a compassionate and beautiful woman named Soraya (whom he marries), and suddenly seems to have a moral compass. As Baba dies of cancer, Amir's kindness becomes apparent. This is not the self-centered, vindictive boy we knew in Kabul. Is it because Baba focuses only on Amir? Because Hassan isn't around?

Despite all the improvements and good deeds, Amir remains silent about his past deeds. Baba dies without Amir ever telling him about the times he betrayed Hassan. Through Amir, Hosseini comments on the difficulties – strange as this may sound – of being a good man. It's harder than one might think. Further, if we zoom out to the international arena of war and conflict, we see too how nations aren't that different from flawed human beings (see "Symbols, Imagery, Allegory: The Question of Allegory" for more).

Amir the Grown Man in Kabul, Afghanistan 2001

Is it possible to both take a step forward and a step backward at the same time? In the world of fiction, it's clearly possible. Back in Kabul, Amir is humble (and clumsy). His time in America has distanced him from the atrocities of war in Afghanistan. Sure, he's seen some stuff on the news, but Tom Brokaw doesn't compare to being surrounded by the real thing.

Back in Kabul, it seems like Amir is finally doing something good in his life. After some misgivings, Amir agrees to rescue Hassan's son, Sohrab, from an orphanage in Kabul. Amir even squares off against a Talib official – who, it turns out, is actually Assef – in order to save Sohrab. This is action instead of inaction; bravery instead of cowardice; selflessness instead of self-absorption. Perhaps this streak of good deeds will atone for his betrayal of Hassan.

On a larger scale, Hosseini is constructing a world where redemption is at least possible. In the universe of the novel, one can return to the site of his misdeeds. And this is important because it suggests nations can atone for mistakes the same as individual human beings (see "Symbols, Imagery, Allegory: The Question of Allegory" for more).

It's almost as if the confident young adult Amir combines with the helpless and misguided childhood Amir. While saving Sohrab, Amir makes a huge mistake and goes back on a promise to Sohrab. As a result, Sohrab tries to commit suicide. We're watching Amir repeat mistakes from the past even as he attempts to put the past to rest. This is Amir at his best and worst – and perhaps this final version of Amir really combines all the previous versions of him. He's weak and blind, but also essentially kind. He's jealous, but in the end only wants to be loved. To sum up: Amir is so frustrating. But we think that's what Hosseini wants us to feel. Even though we want to scream at Amir, he's an utterly human character.