Character Analysis

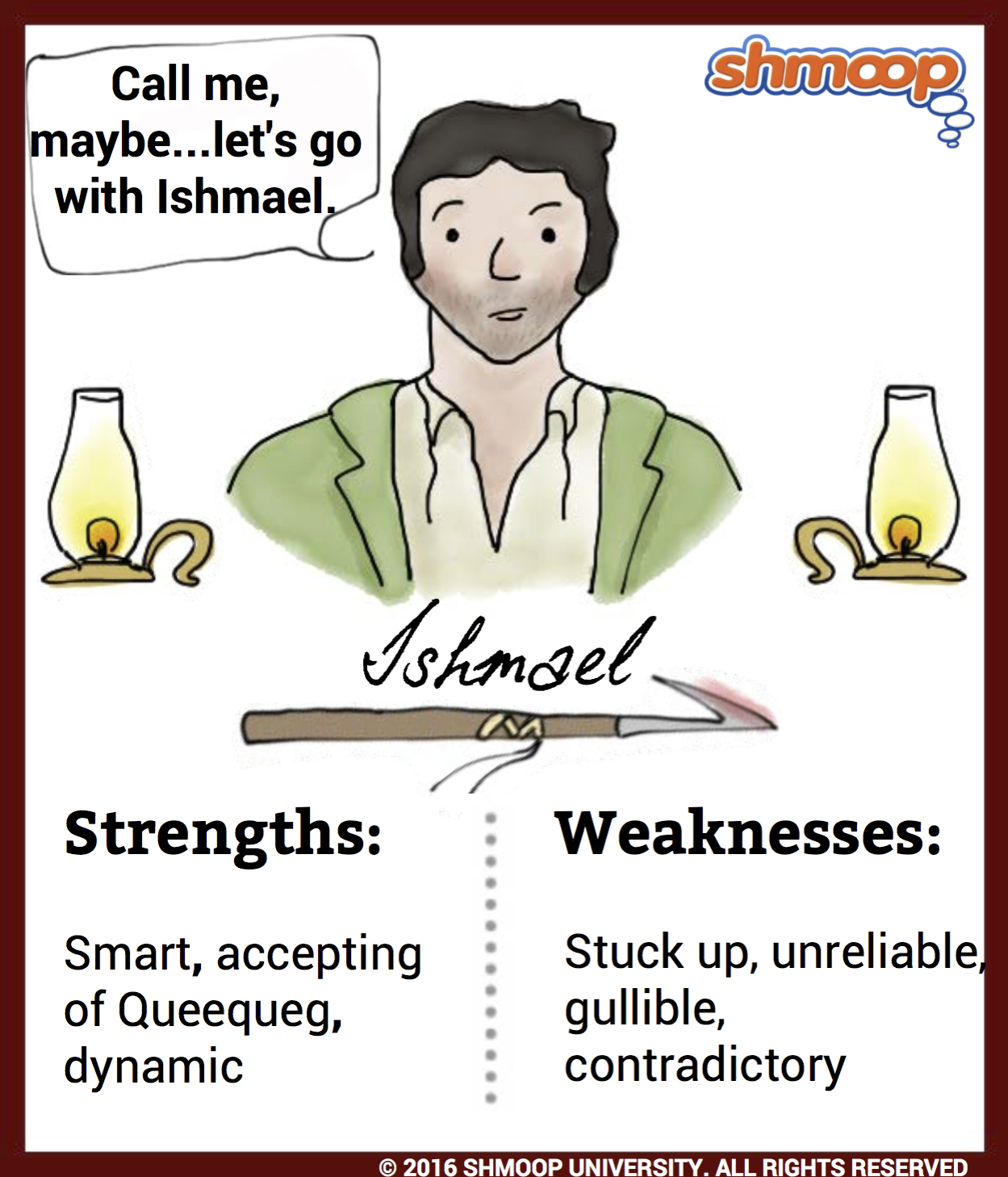

(Click the character infographic to download.)

Call Me What, Now?

It seems pretty easy to identify Ishmael and his role in Moby-Dick: he’s a young, white, American man living in the mid-nineteenth century. He’s educated, a little stuck up, and may once have been schoolteacher. He’s prone to depression, and when he gets really melancholic—or wants to knock off random people's hats—he likes to hire himself out as a common sailor. Convinced that a whaling trip would be the coolest kind of sea voyage (and we’re not saying he’s wrong, there), he joins the crew of the Pequod and tells us, in the first person, the story of his travels.

There. That’s who he is, right? What could be simpler than a story of exploration from an ordinary young sailor?

While you throw your head back and laugh sarcastically about the idea that anything in Moby-Dick could be "simple," we’ll be over here, thinking about Ishmael’s character. That’s if he even has a fully developed character... which we aren’t ready to claim.

If we think of a narrator as a lens through which we view the events of a story, then Ishmael, as a first person narrator, is the one lens that we can actually see. Still, although we’re aware of him, it’s very difficult to figure out what sort of effect supposedly simple Ishmael has on the story he’s telling us. Is he a telescope, a microscope, a kaleidoscope, a clear piece of glass, a dirty and scratched lens? Is he exaggerating, omitting, minimizing, distorting?

Heck, is he telling us his own story or someone else’s—Captain Ahab’s or even the White Whale’s? And can we trust him?

Okay, we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Let’s start at the beginning—the very beginning.

This Must Be Who I Am, Because It Says So On My ID: Ishmael’s Identity Problems

In fact, let’s start with the first sentence of the novel, "Call me Ishmael" (1.1). Even if this is your first time reading Moby-Dick, you’ve probably heard this sentence before. It’s one of the most famous first lines in literature, and people love to quote it. Critics love it, too, and for lots of reasons.

First of all, when the narrator begins with "call me," that implies he’s talking to someone, because the verb is in the imperative or "command form." So, even though the word "you" doesn’t come up, Ishmael is establishing a direct relationship with you, the reader. He gets all buddy-buddy with you right away.

Second, you may also have noticed that this sentence is a bit ambiguous. "Call me so-and-so" is often what people say when the "so-and-so" bit isn’t the name on their birth certificate, as in "Hi, I’m Shawn Corey Carter, but call me "Jay Z." So we don’t really know if Ishmael is actually legally named "Ishmael," or if he’s adopted "Ishmael" as a nickname or a pseudonym, or if he’s just casting himself as "Ishmael" because of the Biblical connotations of that name (see below for more on that).

What’s more, we never hear anyone else in the novel actually call him Ishmael, either—in fact, nobody ever addresses him by name in the novel—so why should we call him that? And we certainly don’t know his last name.

But it's not even as simple as "Well, we don't know this dude's name," because we don’t even know if we don’t know his name. Maybe his name is Ishmael, and we do know it. Ugh! Melville, you're a sadistic genius!

Hey, Ishmael—Wasn’t There Some Famous Guy In The Bible Called That?

We’re glad you asked, and yes, there is. If you feel like reading Ishmael’s whole story, it starts in Genesis 16. But we’ll recap the major points for you:

So, according to the Book of Genesis, Ishmael and Isaac are the sons of Abraham, and they’re half brothers. Abraham’s wife Sarah can’t bear children, so she lets Abraham sleep with her maidservant, Hagar, who gives birth to Ishmael. (The name "Ishmael" means "God hears," if you were wondering.) Later, Sarah does manage miraculously to get pregnant in her old age, and she bears Isaac. Then Sarah convinces Abraham to banish Hagar and Ishmael to the wilderness so that her younger son Isaac can become the next patriarch (God has already decided to establish his covenant with Isaac, anyway.)

Ishmael and Hagar wandered around in the desert, but God takes care of them while they’re there and eventually they make it to safety. According to tradition, Ishmael is the forefather of the Arab peoples, and Isaac is the forefather of the Jewish tribes.

So basically the Biblical Ishmael is a figure in the wilderness, fated for banishment and separation from his earthly father. However, he’s also taken care of by God, and eventually he becomes an incredibly important patriarch... even though it’s in a different world than the one he came from.

So we should be on the lookout for our Ishmael, the one telling us the story of Moby-Dick, to be (1) a fatherless outcast in a barren landscape, (2) really lucky and/or protected by what seems to be divine intervention, and (3) the creator of a new people/world/something awesome by the end.

What does Ishmael create? Read on.

Insert "Whale Of A Tale" Joke Here: Ishmael As Storyteller

Most of the time, Moby-Dick is written in the first person from Ishmael’s perspective. (For more details on which perspectives the novel uses and their significance, see the section on "Narrator Point of View.") Ishmael becomes our point of entry into the story, a regular guy with whom we can sympathize in the midst of Ahab’s crazy epic passions and the complex social makeup of the Pequod.

But he’s also something of a cipher, an empty character who nonetheless holds the key to many of Moby-Dick’s codes. The details of the story pass through him, and he is the shaping influence behind most of the information we get as readers. There don’t seem to be many reasons to distrust him, but he (or at least one of the narrating voices in the novel) is awfully concerned with making sure we think the story is realistic:

I do not know where I can find a better place than just here, to make mention of one or two other things, which to me seem important, as in printed form establishing in all respects the reasonableness of the whole story of the White Whale, more especially the catastrophe. For this is one of those disheartening instances where truth requires full as much bolstering as error. (45.7)

Over and over again in this novel, Ishmael takes breaks from the plot to explain in detail (lengthy, loving detail) aspects of whale biology or sailing ships that may seem incredible to his readers. He’s obsessed with convincing the reader that the story is "reasonable": that whales can be vicious and attack their hunters; that compasses can be demagnetized; that an individual whale can have a personality and a nickname.

But, wait! What do we call it when someone keeps insisting that something we hadn’t even thought of questioning is true? Does the line "methinks the lady doth protest too much" fit here? The person who appears to need convincing that the story is fact and not fantasy is Ishmael himself.

Speaking of fact versus fantasy, this brings us to some thoughts about what Ishmael creates. If the Biblical Ishmael builds a new tribe and nation, Melville’s Ishmael produces a work of art, creating a new world as he spins his yarns.

Don’t Be Alarmed If I Fall Head Over Harpoon: Ishmael And Queequeg

Our analysis of Ishmael wouldn’t be complete without a few thoughts about the bromance (or plain ol' romance) between Ishmael and Queequeg. Although it fades into the background for the climactic scenes of the novel (and during all those "let me tell you all about whaling" chapters), Ishmael’s bond with Queequeg gives us our first insight into who Ishmael really is, when he’s not watching life from the sidelines.

Seriously, what is going on with these crazy kids? Are they lovers? Are they friends? Are they something in between? The affection they feel for one another is made even more complicated as Queequeg becomes a mentor to Ishmael due to his greater experience with whaling. And, of course, Ishmael’s reaction to Queequeg’s ethnicity, "savage" tribal culture, and paganism makes it even harder to figure out what these guys are to each other.

Let’s review a few of the lessons we learn about Ishmael from his reactions to Queequeg. Even before Ishmael meets Queequeg, he’s frightened of the strange harpooner. When Ishmael eventually sees Queequeg, the man’s tattooed body and racial difference terrify him. But after just one night spent sharing a bed (do we cue the "bow chicka bow bow" music here? we're not sure!) all Ishmael’s opinions change, and he’s the biggest Queequeg fan of them all. He’s fallen head-over-heels for the guy. He’s even willing to worship Yojo, Queequeg’s god. So we’ve learned that Ishmael doesn’t know everything... and that he can be easily convinced to change his opinions.

Whether this means that Ishmael is open-minded and able to see past stereotypes or weak-willed and easily influenced you’ll have to decide for yourself. Sometimes Ishmael expresses enlightened attitudes about race that seem more like 21st Century thinking than 19th Century prejudices:

And what is it, thought I, after all! It’s only his outside; a man can be honest in any sort of skin. (3.54)

Ignorance is the parent of fear... (3.55)

What’s all this fuss I have been making about, thought I to myself -- the man’s a human being just as I am; he has just as much reason to fear me, as I have to be afraid of him. (3.69)

But when you take Ishmael's statement about Queequeg (which are, as we said, awesome) and direct them towards other subjects (like, say, creepy Captain Ahab) they start to look a little spineless or gullible... or at the very least a little innocent.

Sure, a "man can be honest in any sort of skin"... but does that mean that "a man with crazy-eyes and a huge freakin' scar should be trusted with your life"? It's fair enough to state that "ignorance is the parent of fear," but what about the real fear that can be created from having full knowledge of the fact that you're on board a single-minded psycho's revenge ship?

But that's our boy Ishmael. He's a bundle of contradictions and human fallibility... and a testament to Melville's character-writing brilliance.