Where It All Goes Down

Middle-earth: Gondor, Dunharrow, the Paths of the Dead, Pelargir, the Field of Cormallen, Isengard, Bree, the Shire, the Grey Havens

In The Fellowship of the Ring, we get this outward movement from the hobbits' home of the Shire (which is about the homiest home that ever homed) through the lands of the elves (Rivendell and Lothlórien) and the dwarves (Moria) to a place of uncertainty (Amon Hen, where the Fellowship splits up). The setting in The Fellowship is all about contrast between the place where Frodo, Sam, Merry, and Pippin came from and the places they're going.

The Return of the King has almost an opposite movement. We start out with the grand, ancient settlements of men: Dunharrow, where the people of Rohan seek refuge and which is surrounded by statues so old that no one knows who made them; and Minas Tirith, the White City, the capital of Gondor, which has been one of the goals of the series ever since Boromir started bragging about it in the first book.

Since we keep getting told over and over again that the age of elves is passing and they all need to head into the West, we know that men are going to inherit Middle-earth. So it makes sense that the emphasis of the last book in the series would be on the dwellings of humans rather than on the forests and valleys of the elves.

And from these grand places, we move back to the more familiar territory of the Shire, where the Quest started out. Tolkien gives The Lord of the Rings series a strong sense of structure and of narrative closure by finishing The Return of the King in the same place that The Fellowship of the Ring began.

The World of Men

Dunharrow and Gondor both show us something interesting about the people who live there: Dunharrow is an ancient mountain fortress with a history that even the people of Rohan (who actually use the space) do not know. The fact that the people of Rohan can rely on the fortress's primitive strength and protective power even though they do not fully understand where it comes from says something about their own adaptability. The people of Rohan are practical: they use what they have, without worrying too much about history.

By contrast, Minas Tirith is a city with lots of history that just about everybody in Gondor knows. We know that Minas Tirith dates back to Elendil and his line, who were exiles from the land of Númenor from back in the days when men and elves were much closer buddies.

Minas Tirith starts out as a center of high human culture (as opposed to the primitivism of Dunharrow). At the same time, Minas Tirith is now half empty. Its people have diminished and dwindled in learning and in fitness. There has been degeneration in Gondor that Aragorn's return (with his foxy elvish bride) just might reverse.

The beauty of Gondor's architecture contrasts with the damage the war has done on its buildings and people. After Sauron has his way with the city, it's just plain ravaged, top to bottom. There is a lot to rebuild in Gondor, not just literally but also metaphorically, after its long, slow, king-less decline.

The World of Hobbits

When we started out the series, the settings were all stark contrasts: the Shire could not be more different from Rivendell or Lothlórien or even Khazad-dûm. But how about now, at the end of the series? Well, the Shire has changed. It may still be a homey place mostly removed from the rest of the world, but the Shirefolk have had to fight back an invasion of outsiders.

Still, these "outsiders" are half-human half-goblin bullies under the control of a weakened Saruman. They're not orcs from Mordor or anything like that. And even after their unpleasant experiences with these thieves, the Shirefolk still can't understand the grand Ring quest that Frodo and his friends went on, nor do they recognize Frodo's amazing heroism. They have changed, but not all that much. And when Sam starts replanting all the trees in the Shire and helping to oversee the building of new tunnels and homes, he is bringing the Shire back to its original homey state, as we saw it way back in The Fellowship of the Ring. The Shire soon becomes a comfortable haven of ordinary hobbit life once more.

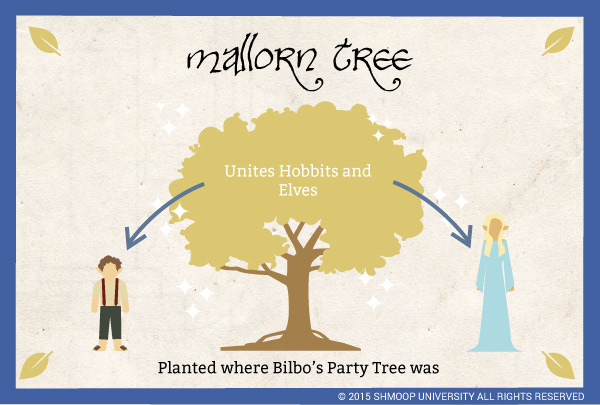

But even if the Shire has become a comfortable home for hobbits again, it still shows new signs of elvish influence that bring it closer to Lothlórien or to Minas Tirith than it was in The Fellowship of the Ring. There is the mallorn-tree, the gift of the lady Galadríel, which Sam plants in place of the cut-down Party Tree after the Scouring of the Shire. This tree is a reminder of fading Lothlórien. The fact that it grows and thrives right at the heart of the Shire proves that the Shire has been touched by elvish magic at last.

(Click the infographic to download.)

Other signs of this change in the Shire's setting include Merry and Pippin's unusual height and fine armor, which remind the hobbits of the great deeds these two have done in far-off wars. And the hobbits know that the king has returned to his seat in Minas Tirith at last, and they are his loyal subjects. We also learn in the appendices that Sam's own eldest daughter, Elanor, travels to Minas Tirith to be a handmaiden to Queen Arwen.

All of these details go to show that, where there was once a deep cultural barrier between the Shire and the great places of Middle-earth, this boundary is starting to come down. The Shire is still homey and comfortable in a deeply hobbity way. But it's not so cut off from grand locations such as Minas Tirith any more.

And that's how it should be, isn't it? In a way, as Sauron gained power, the different regions of Middle-earth had to come together in an alliance against him. Where they were once quite separate, even insular, they are now much more united. By the end of The Return of the King, Middle-earth feels like much more of a community, rather than a mysterious, vast, and divided realm.