Plant and Fungal Viruses

For the most part, this chapter is going to only talk about animal viruses. "But," you say, "What about those really cool carrot viruses or viruses that infect fungi or bacteria?" Well, calm down. We're getting to it.

Plant and fungal viruses are very similar to animal viruses; they fall in the same 6 types of genomes that we mentioned in the Virus Genomes section, and they're either helical or icosahedral in structure, though very few have envelopes.

One of the largest differences, though, between animal viruses and plant, bacterial, and fungal viruses (aside from their political differences) is that plants, bacteria, and fungi all have cell walls, which creates an extra barrier that viruses must navigate. Plant viruses get around this by being transmitted primarily through vectors. A vector is an organism that carries a virus from point A to point B. In animal viruses, vectors are usually insects (curse you, mosquitos!). But because plants don't have tasty blood, plant viruses use a variety of vectors, such as:

Aphids Damaging a Plant

Alternatively, a virus can enter a cell through physical damage, such as when you tear blades of grass with a lawnmower, or when you punch rhododendrons, which isn't as fun as it sounds. Entry through physical damage is called "mechanical transmission," though this isn't limited to machines causing transmission. This is just a coincidence, and not another reason to destroy SkyNet (but seriously…destroy it). "Mechanically transmitted viruses" include bromoviruses and tobamoviruses.

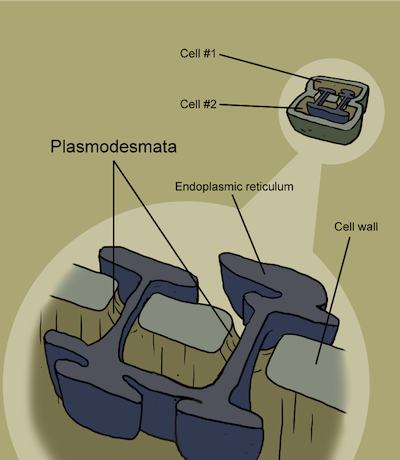

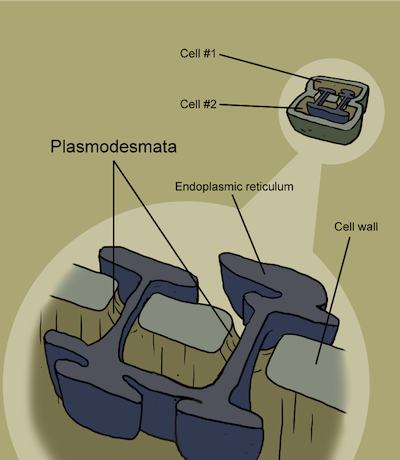

Plasmodesmata structure

Once in the plant, the virus can transmit from cell-to-cell using channels called plasmodesmata. These are small pores that plant cells use to communicate, like pay phones, but cleaner. The center of the figure above is a cell wall, and the lines connecting one side to the next are endoplasmic reticulum, organelles spanning the plasmodesmata. Viruses hijack the structure of plasmodesmata and make the channels bigger to allow for easier transmission. Oooh…stretchy.

Fungal viruses have the same problem as plant viruses, finding jeans that fit. They also have the problem of getting through a cell wall. Fungi don't have the nutritional value of plants, so vector transmission is uncommon, because nobody likes fungi, even though they're fun guys.*

The transmission of fungal viruses is kind of weird—many of these viruses don't have genes for transmitting themselves from cell to cell. In fact, the narnavirus family doesn't even produce a capsid protein, as its replication cycle is completely intracellular. It is spread through spores in mating or vertically from mother to daughter cells. In essence, the fungal virus is lazy and lets the host do most the work of spreading itself around.

*We at Shmoop would like to apologize for that last joke. The writer of that joke has been fired, and we have replaced them with a joke-writing cyborg we call PunBot3000.

Plant and fungal viruses are very similar to animal viruses; they fall in the same 6 types of genomes that we mentioned in the Virus Genomes section, and they're either helical or icosahedral in structure, though very few have envelopes.

One of the largest differences, though, between animal viruses and plant, bacterial, and fungal viruses (aside from their political differences) is that plants, bacteria, and fungi all have cell walls, which creates an extra barrier that viruses must navigate. Plant viruses get around this by being transmitted primarily through vectors. A vector is an organism that carries a virus from point A to point B. In animal viruses, vectors are usually insects (curse you, mosquitos!). But because plants don't have tasty blood, plant viruses use a variety of vectors, such as:

- Bacteria

- Fungi

- Nematodes

- Arthropods

- Arachnids

Aphids Damaging a Plant

Alternatively, a virus can enter a cell through physical damage, such as when you tear blades of grass with a lawnmower, or when you punch rhododendrons, which isn't as fun as it sounds. Entry through physical damage is called "mechanical transmission," though this isn't limited to machines causing transmission. This is just a coincidence, and not another reason to destroy SkyNet (but seriously…destroy it). "Mechanically transmitted viruses" include bromoviruses and tobamoviruses.

Plasmodesmata structure

Once in the plant, the virus can transmit from cell-to-cell using channels called plasmodesmata. These are small pores that plant cells use to communicate, like pay phones, but cleaner. The center of the figure above is a cell wall, and the lines connecting one side to the next are endoplasmic reticulum, organelles spanning the plasmodesmata. Viruses hijack the structure of plasmodesmata and make the channels bigger to allow for easier transmission. Oooh…stretchy.

Fungal viruses have the same problem as plant viruses, finding jeans that fit. They also have the problem of getting through a cell wall. Fungi don't have the nutritional value of plants, so vector transmission is uncommon, because nobody likes fungi, even though they're fun guys.*

The transmission of fungal viruses is kind of weird—many of these viruses don't have genes for transmitting themselves from cell to cell. In fact, the narnavirus family doesn't even produce a capsid protein, as its replication cycle is completely intracellular. It is spread through spores in mating or vertically from mother to daughter cells. In essence, the fungal virus is lazy and lets the host do most the work of spreading itself around.

*We at Shmoop would like to apologize for that last joke. The writer of that joke has been fired, and we have replaced them with a joke-writing cyborg we call PunBot3000.